Notes from the Field

Notes from the Field

FSE Senior Fellow, Emeritus, Walter Falcon shares observations from Iowa on weather, farming, politics and more.

Halloween has come and gone, the fourth crop of alfalfa is in the barn (without having been rained upon), the soybeans are combined, and the corn is currently being harvested and will soon be in someone’s gas tank. All of which means that my annual field report is overdue. This series of essays, which began as a lark more than a decade ago, is now my most-read publication! This 12th edition, however, is different from its predecessors. In prior years I have reported that I was a Professor of International Agricultural Policy and Economics at Stanford who happened also to own a family farm in Iowa. But 50 years after joining the Stanford faculty, I have fully retired. I write now as a full-time Iowan who is (partly!) adjusting to a new lifestyle. Fortunately, I had a few papers in the pipeline that helped ease the process of transition. I am also enjoying the quiet of the farm. The year has also given me time to recall earlier experiences that needed both time and distance for me to put comfortably on paper. (I am hoping this essay will appear before Christmas.)

The 2022 agricultural year was a most unusual one. The Ukraine war added volatility to global grain markets. The doubling of nitrogen fertilizer prices from $750 to $1,500 per ton, coupled with much higher hybrid seed costs, caused a large substitution of soybeans for corn. And widespread drought across the United States curtailed production of both grain and roughage crops.

Despite the troubling global context, the situation on our farm in east central Iowa was near optimal. Rainfall was slightly less than normal but was perfectly timed. We went heavily toward soybeans (away from corn) and yields were spectacular. “Normal” bean yields for our farm are in the 45-50 bushels per acre range. This year the yield was 71 bushels per acre. The beans were sold to the local Cargill crushing plant directly from the field, so this measurement (at 11.5 percent moisture) is precise. Moreover, bean prices were very high--$13.25 per bushel-- delivered to the plant only 15 miles from the farm. Two years before the comparable price was $8.25 per bushel.

The widespread drought in the South and West had significant impacts on regional hay and straw markets. We have been receiving more than $200 per ton for hay f.o.b. the farm, , and with four cuttings and few costs other than baling, alfalfa proved also to be a big money maker. The corn story is yet to be told, but it appears to be a good, but not record crop in terms of yield. We budget on the basis of 240 bushels per acre, but my conjecture is that yields will be in the 215 to 220-bushel range. In part, this reduction occurred because it is the second year for corn on this ground. Deer also feasted at our expense, raising havoc with quite a large area. (It turns out that our neighbor developed a habitat area for wildlife as part of a new conservation initiative. He provided the bed for the deer; we apparently provided the breakfast.) We did not skimp on fertilizer, but the extremely high costs of nitrogen fertilizer caused many farmers to curtail nitrogen applications. Where there was adequate moisture, significant portions of U.S. corn acreage simply did not reach its full potential. To complete the price trifecta, corn prices are also high--$6.10 per bushel delivered to the local ADM ethanol plant.

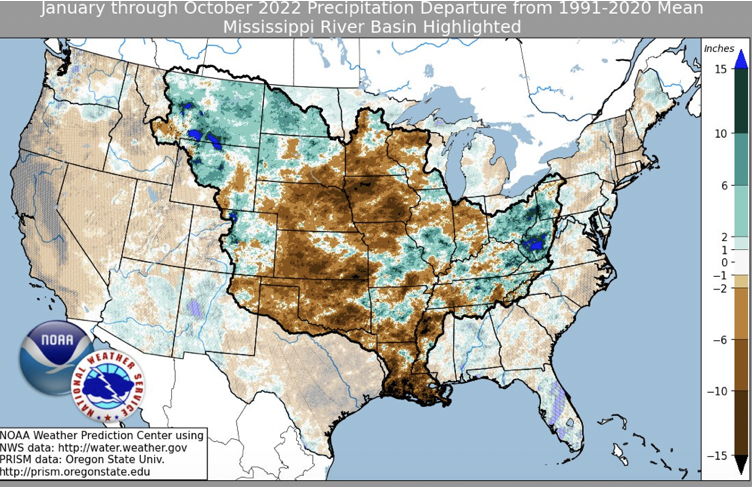

We are fortunate in being close to a large processing center (Cedar Rapids). Trucking costs have skyrocketed, and a major drought over the Mississippi Valley is raising havoc with river flows. The current flow of the Mississippi River is the lowest since the dust bowl years of the 1930s This dimension of climate change has sharply curtailed barge movements. A significant portion of Iowa corn and soybean production goes by barge to Gulf ports for export. This curtailment is beginning to affect the relationship been cash and futures prices, and will also have adverse effects on much of the fertilizer, road salt and other bulk commodities that come North via the barge back-haul.

Lest anyone think that this is a great year to get started in farming, however, he or she needs to look at macro policy. Inflation and interest rates are really squeezing farmers. For example, a new John Deere combine harvester costs $950,000, unless one opts for a better German machine that costs $1.5 million. With diesel at $5 per gallon, it costs in excess of $2,000 for the daily fill of the fuel tank. Thirty-year fixed interest rates for land purchase have doubled in the last 18 months, and now exceed 6 percent. Despite these rates, land prices are rising, not falling, as are cash rents. Locally, farms are selling in the $15,000 per acre range, and cash rents are running between $250-$300 per acre depending on land quality. Interestingly, in 2008, another price-spike year, farms were selling for less than $5,000 per acre and corn prices were at $5.30 per bushel.

The past 5 years has seen large changes in the way hay is being harvested—from 75-pound small rectangular bales moved mainly by hayrack and hand, to 800-pound bales moved by skid loaders. These changes have in turn made many older barns with overhead hay mows obsolete for storage. As a consequence, we splurged and over the summer erected a new 60 x 80 feet multipurpose shed that can house both hay and larger machinery. Its design is something quite different—at least for us. It has a wooden frame, metal sides, steel tubular trusses and a canvas hoop roof. The roof has a 15-year guarantee—forever, from our 86-year-old perspective. The shed itself is huge, and it is already too small!

Three events seem to be causing most of the excitement locally this summer—the churches, the fairs, and the elections. The small rural churches that dot the Iowa landscape seem to have emerged from their covid hibernation. For the Methodists, this has taken the form of a contentious fight between more liberal bishops and more conservative congregations that will likely split the United group into two separate factions. Several issues are involved, but most notably the question of how literally the bible is to be interpreted and the possible role, if any, for gays within the clergy. Since so much of the community activity centers around the church, the split is causing considerable agony. The real battle is yet to come: to which group do the church assets belong?

The fairs now are also back in full swing. The Iowa State Fair set all kinds of records. More than a million people attended in a state of only 3.2 million people; super-bull “Albert” checked in at 3,042 pounds; and the champion 4-H market steer, weighing 1,400 pounds, sold for $135,500. (Talk about high-end hamburgers!) The most interesting (disgusting?) new fair food was a pork tenderloin sandwich made with two glazed doughnuts as the bread. Science’s “Fair Warning,” showing the possible link between hog shows and flu viruses, has yet to make the Iowa press.

Iowa, like the rest of the country, seems overrun with political ads. The forever Iowa senator Charles Grassley (now 89) is in a surprisingly tight race, but it appears that Iowa will vote overwhelmingly red this year. I am both amused and offended by the strident ads that openly accuse opponents of trying to convert Iowa into California or of being a “Pelosi Puppet”. The current Governor is running for re-election, and one of her ads praises Iowans for “knowing right from wrong and the difference between boys and girls”. Donald Trump is little discussed, but Trumpism is alive and well throughout the state.

Unfortunately, one useful local institution did not survive the pandemic and demographic change. The 8 am gathering of farmers at the tavern in nearby Waubeek is no more. Covid caused the initial disruption, but deaths, moves to nursing homes, and migrations to the South decimated the ranks of the regular attendees. No one misses the terrible coffee; everyone misses the conversation and gossip.

Farmers need to be agronomists, veterinarians, carpenters, mechanics………. Being a lawyer would not hurt either. Consider this implausible case—yet 100 percent of it is true. We rent one of our pastures to a neighbor, who uses it to graze a bull and 30 cows. That pasture adjoins another pasture that we use for our own cow herd, plus a bull that we rent annually. In what can only be described as a harem dispute, the neighbor’s bull broke the fence between the two pastures, prompting our own version of a bull fight. In addition, that night we had a flash flood. Our rented bull, who had since got into the pasture we rent attempted to cross the raging creek, literally got stuck and injured his leg so badly that he could not walk and had to be put down. This seems like a cock and bull story, but it is precisely what in fact happened. The legal question is who pays for the dead bull? Is it the farm insurance policy? The renter whose bull broke the fence? The owner of the bull? Or the Falcon farm that had rented the bull? Interestingly, all the above got settled very amicably (in less than 10 minutes) on the following basis. Since no farmer negligence was involved, Iowa law says that neither the insurance company nor the neighbor was liable. The owner of the bull and we ended up sharing the loss 50/50 after solving the equally difficult problem of what a good purebred breeding bull was worth. The biggest problem, however, was loss of the bull per se. His loss was much more than a tax deduction. This year he sired an extraordinary group of calves. His progeny were small and not even the first-year heifers needed assistance in calving; moreover, the entire cow herd less one all calved within 3 weeks. That we should be so lucky as to find a comparable sire for next year.

The real lawyers at both the Iowa and U.S Supreme Courts were busy with Iowa livestock as well. We currently do not raise hogs, but our neighbors do. Confined pork systems often emit strong odors, creating a pollution effect for anyone down wind. The Iowa court held that growing livestock was constitutionally protected, and that bringing suits against farmers for these odors was unconstitutional. It seems to me that the Court got perilously close to giving farmers a constitutional right to pollute! And if livestock production is guaranteed by the Iowa Constitution, so too must be the growing of crops. By analogy, does this mean that farmers cannot be sued for fertilizer runoff—perhaps Iowa’s greatest environmental problem? Stay tuned.

The fight between animal rights activists in California and pork producers in Iowa, mentioned last year, is now being heard by the U.S. Supreme Court. The case turns out to be quite important. California consumes 13 percent of all the pork produced in the U.S. Three-fourths of these pork products are grown in other states—importantly from Iowa. The issue is whether California can ban shipments from other states whose farmers do not provide 24 square feet to sows versus the more common 16 square feet typically found in Iowa. There are some important issues of detail—monitoring, enforcement, and penalties—but the central issue is whether the California referendum is unconstitutional because it violates the interstate commerce clause of the U. S. Constitution. My betting is that the Court will rule the referendum unconstitutional, but only fools predict how this Court will rule on almost anything.

I close with a non-event. Few people realize that the growing of hemp—supposedly for medicinal and industrial purposes—is embraced under the current U.S. farm legislation. I frequently am asked if we grow hemp, and the answer is no. Some thought that hemp was the new get-rich crop. It turns out, however, that supply and demand also work for hemp. Despite supply regulations, supplies far exceeded demand and hemp prices crashed. Better to stick with corn, soybeans and alfalfa!

All signs point to a long and cold winter. Given that the year thus far has been near perfect, I suppose we deserve it.

Walter P. Falcon is Farnsworth Professor of International Agricultural Policy and Economics, Emeritus. He and his wife, Laura, reside on their farm near Marion, Iowa. (wpfalcon@stanford.edu)