As authors of “China’s aquaculture and the world’s fisheries” (Cao et al., Science, 2015), we would like to dispute several claims presented in “A revisit to fishmeal usage and associated consequences in Chinese aquaculture” (Han et al.,§ Reviews in Aquaculture, 2016), as the latter seriously misrepresents the intent and substance of our Science paper.

In their review, Han and colleagues argue that although China’s aquaculture volume continues to grow, its fishmeal usage remains stable, and the sector will therefore indirectly reduce pressure on wild fish stocks worldwide. In the process, they claim that we do not acknowledge the important contribution of the Chinese aquaculture sector to global food supply. They also claim that we criticize the sector’s excessive use of fishmeal and that we trot out the “Chinese aquaculture threat” theory. We are aware of Han and colleagues’ comprehensive work on substitution and sustainable sourcing of fishmeal and fish oil in aquaculture, which is clearly aligned with our perspective. However, we believe that the underlying intention of our Science paper has been seriously misinterpreted, and there are several inaccuracies in their review that are important to clarify and correct.

Here, we emphasize and reiterate the key points in our paper: China’s impact on marine ecosystems and global seafood supplies is unrivaled given its dominant role in fish production, consumption, processing and trade. Its aquaculture sector, by far the world’s largest, is of enormous global importance for meeting the rising demand for food and particularly for protein. Understanding the implications of the industry’s past and current practices is important for managing its future impacts and improving its sustainability. The country’s nonspecific and erroneous reporting of fish production and trade makes it especially difficult to access the impact of China’s aquaculture and aquafeed use on global wild fisheries. We unraveled the complicated nature of China’s expanding aquaculture sector and its multifaceted use of fish inputs in feeds, to the best of our abilities. We also developed a roadmap for China’s aquaculture to become self-supporting of fishmeal by recycling processing wastes from its farmed products as feed. We showed that if food safety and supply chain constraints can be overcome, extensive use of fish processing waste in feeds could help China meet one-half or more of its current fishmeal demand, thus greatly reducing pressure on domestic and international fisheries. In addition, we suggested China to commit to stricter enforcement of regulations on capture fisheries and to responsible sourcing of fishmeal and fish oil, as well as to improve its data reporting and sharing on the status of fisheries stocks, aquaculture practices, production, and trade.

We would like to respond specifically to the following points in Han et al (2016):

1. “Role of China’s aquaculture in meeting the rising demand for fish at home and abroad is not acknowledged by Cao et al., 2015.”

Our response: Our paper conveys a clear message that China’s aquaculture industry is by far the world’s largest and of great importance for meeting the rising domestic and global demand for fish and protein.

2. “China contributes more than 60% to the global aquaculture output and is expected to contribute 38% to the global food fish supply by 2030, however costs only 25-30% of the world fishmeal. The above facts are contradictory to the views expressed that Chinese aquaculture is a threat to the world’s wild fish resources (Cao et al., 2015). China’s aquaculture and aquafeed industry have some special features leading to the steady fishmeal usage, which consequently does not impose additional stressors on the world wild fish stocks, drawing a conflicting conclusion to that found in Naylor et al. (2000, 2009) and Cao et al. (2015).”

Our response: Our paper clearly indicates that China is a net contributor of fish (fed fish). The table in our paper shows that from 5 million metric tons (mmt) forage fish equivalents, 14.4 mmt of finfish and shrimp were produced in 2012 (21 mmt is the total but with the non-fed carp species having been subtracted). Moreover, we write: “If China is to increase its net production of fish protein, its aquaculture industry will need to reduce FCRs and the inclusion of fish ingredients in feeds and to improve fishmeal quality”. Thus, we are not asserting that China consumes more fish than the fed fish it produces, but rather we are challenging the industry to further increase its current net production of fish protein.

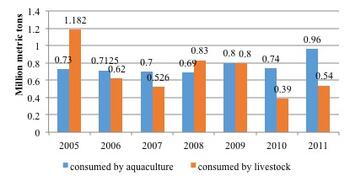

While China’s fishmeal import has been stable at a level of 1-1.5 mmt over the past decade, it should be noted that the use of fishmeal for aquaculture has increasingly been diverted from the livestock to aquaculture sector. There are no official statistics specifying in which sector the fishmeal is used. One market trend study published in Chinese stated that the share of fishmeal use for aquaculture in China has exceeded the share used by livestock since 2010, growing from 38 percent (0.73 mmt) in 2005 to 64 percent (0.96 mmt) in 2011 (see Fig. 1). Our observation is consistent with the literature that supports a trend of shifting in fishmeal use from other sectors towards aquaculture (De Silva and Turchini, 2008).

We agree that China has made remarkable progress in identifying alternative ingredients for substituting fishmeal and fish oil in aquafeeds, especially for low-trophic level species. We are more concerned with the high inclusion rate of fishmeal in high-trophic carnivorous species and using trash fish as feeds for aquaculture.

Figure 1. Fishmeal use in China (Chen 2012)

3. “China’s domestic fishmeal production is based on processing waste and trash fish.”

Our response: Han and colleagues confirmed our observations. However, we are more concerned with the impacts of harvesting low-value trash fish species on the structure and functioning of marine ecosystems and global food security (Smith et al., 2011). Multi-species (non-targeted) catch, commonly designated as “marine fish nei” (nei: not elsewhere included) by FAO, surpasses the catch of any individual species in China’s ocean capture fisheries. Combined with by-catch and other poor quality fish from targeted fisheries, it is a major contributor to what the international research community often refers to as low-value “trash fish”. Although these fish resources are considered to be “low-value” in the market, they are derived from fisheries that have a higher social value for direct human consumption and marine ecosystems (Tacon et al., 2006). Whilst it is true that trash fish includes naturally small fish, it is also true that significant numbers of juvenile fish are also taken and, in combination with poorly regulated fisheries, this take of juvenile fish undoubtedly contributes to the poor status of many fish stocks. Virtually all of the fish hauled out of the ocean by Chinese vessels are put to economic use, first for human consumption, and then for feeds and other purposes. Large amounts of trash fish are being used for fishmeal production and China’s high-value marine aquaculture uses around 3 mmt of trash fish each year for direct feeding. Notwithstanding the improvements in feed efficiency demonstrated by Han et al relieves the issue of overfishing, China’s increased use of trash fish for aquaculture deserves further investigation.

4. Data quality issue: “Survey data in the studies of Chiu et al. (2013) and Cao et al. (2015) from only four provinces of China, Guangdong, Shandong, Zhejiang, and Hainan don’t fully represent the status of Chinese aquaculture, in particular freshwater aquaculture.”

Our response: We present data and analyses based on not only primary field surveys and observations from the four major aquaculture producing regions in China, but also on national production and trade statistics, and scientific papers from the Chinese and international literature. We use the same national fisheries statistics databases as Han and colleagues do. In terms of our field data collection, Guangdong and Shandong provinces are the top two aquaculture producers in China. The four provinces together account for over one third of China’s aquaculture production and one quarter of its freshwater aquaculture output by volume. The field data were based on in-depth field surveys conducted by Stanford University and the EU-FP7 Sustaining Ethical Aquaculture Trade (SEAT) project during the year of 2010-2012. The surveys focused on carp, tilapia, and shrimp systems, which represent three of the largest aquaculture sub-sectors in China along a spectrum of low- to high-valued species and account for over 50% of the country’s aquaculture output by volume. So we are confident that the provinces that we selected are representative for the farming systems in focus.

As highlighted in both publications, obtaining this type of data from China is notoriously difficult. Our reliance on information from only four provinces is due to the lack of publicly available studies of trash fish catches in other studies and the lack of regular monitoring of catches and stock status. Given the uncertainty involved and the difficulty in obtaining more accurate data, we have endeavored to provide the best available data from primary and secondary sources in order to demonstrate how dependence on fishmeal from targeted and non-targeted fisheries can be substantially reduced. In order to bring as much rigor to the analysis as possible, we have also incorporated uncertainty analysis via Monte Carlo simulation. Many scientists agree that this is a fair approach and our analysis is valid.

Closing Remarks

There is no question that China’s aquaculture will remain a dominant industry domestically and internationally in the future. At the global scale, the sector has expanded at an annual rate of 8.8% during the past three decades—faster than any other animal food sector—and it currently accounts for about half of all fish produced for human consumption. Within this dynamic context, China’s aquaculture sector remains an important “black box” for many scientists and policy analysts with respect to farming practices, aquafeed demand, domestic fishmeal production, trash fish consumption, and impacts on global capture fisheries. Our paper helps to crack open this black box, and it provides an integrated and innovative perspective on the status and trends of China’s aquaculture development. If Han and colleagues have more accurate data to share, we would be more than happy to take these data into account in our attempt to map the fishmeal use in China and steer China’s aquaculture industry towards best practice. To that end, we recommend that China establishes a public process for data reporting and sharing on fisheries stock status, aquaculture practices, production, and trade.

We hope these responses have clarified the misinterpretations of our paper by Han et al. (2016), and that these points can be corrected accordingly. It is important to note that we, the study authors, and Han et al. are clearly united in the recognition that China’s aquaculture industry is a key component of meeting the country’s and the world’s growing protein needs. We also agree on the importance of sustainable aquaculture practices in China that safeguard the health of wild fisheries at home and abroad. We truly believe in China’s commitment to the development of more sustainable and responsible aquaculture practices based on ecological principles. We look forward to a more positive intellectual exchange with Han and colleagues in the future as we strive for this common goal.

Ling Cao[1],*, Rosamond Naylor1 , Patrik Henriksson2,3, Duncan Leadbitter4, Max Troell3, 5, Wenbo Zhang6

[1]Center on Food Security and the Environment, Stanford University, Stanford, CA 94035, USA. 2WorldFish, Penang, Malaysia 3Stockholm Resilience Centre, Stockholm University, 106 91 Stockholm, Sweden. 4University of Wollongong, Wollongong NSW 2522, Australia. 5The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, 104 05 Stockholm, Sweden. 6Shanghai Ocean University, Shanghai 201306, China. *Correspondence should be addressed to L. Cao (email: caoling@stanford.edu).

§Han, D., Shan, X., Zhang, W., Chen, Y., Wang, Q., Li, Z., Zhang, G., Xu, P., Li, J., Xie, S., Mai, K., Tang, Q., De Silva, S. (2016), Reviews in Aquaculture. Article in Press

References

Cao, L., Naylor, R.L, Henriksson, P., Leadbitter, D., Metian, M., Troell, M., & Zhang, W. (2015). China's aquaculture and the world's wild fisheries. Science, 347(6218), 133-135.

Chen, M. (2012). Fishmeal Market Analysis and Outsourcing Strategy in 2012 (in Chinese). Fisheries Advance Magazine, (4), 95–97. Available at: http://d.wanfangdata.com.cn/Periodical_hyyyy-scqy201204059.aspx.

Chiu, A., Li, L., Guo, S., Bai, J., Fedor, C., Naylor, R.L. (2013). Feed and fishmeal use in the production of carp and tilapia in China. Aquaculture, 414, 127-134.

De Silva, S. S., and Turchini, G. M. (2008). Towards understanding the impacts of the pet food industry on world fish and seafood supplies. Journal of agricultural and environmental ethics, 21(5), 459-467.

Han, D., Shan, X., Zhang, W., Chen, Y., Wang, Q., Li, Z., Zhang, G., Xu, P., Li, J., Xie, S., Mai, K., Tang, Q., De Silva, S. (2016). A revisit to fishmeal usage and associated consequences in Chinese aquaculture. Reviews in Aquaculture. In press.

Naylor, R.L., Goldburg, R.J., Primavera, J.H., Kautsky, N., Beveridge, M.C., Clay, J., Folke, C., Lubchenco, J., Mooney, H. and Troell, M. (2000). Effect of aquaculture on world fish supplies. Nature, 405(6790), 1017-1024.

Naylor, R.L., Hardy, R.W., Bureau, D.P., Chiu, A., Elliott, M., Farrell, A.P., Forster, I., Gatlin, D.M., Goldburg, R.J., Hua, K., Nichols, P.D. (2009). Feeding aquaculture in an era of finite resources. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 106(36), 15103-15110.

Smith, A.D., Brown, C.J., Bulman, C.M., Fulton, E.A., Johnson, P., Kaplan, I.C., Lozano-Montes, H., Mackinson, S., Marzloff, M., Shannon, L.J., Shin, Y.J. (2011). Impacts of fishing low–trophic level species on marine ecosystems. Science, 333(6046), 1147-1150.

Tacon, A.G.J, Hasan, M.R., Subasinghe, R.P. (2006). FAO Fisheries Circular. No.1018; FAO 2010. FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture Report. No. 949.