Synthetic fertilizers have dramatically

increased food production worldwide. But the unintended costs to the

environment and human health have been substantial. Nitrogen runoff

from farms has contaminated surface and groundwater and helped create

massive "dead zones" in coastal areas, such as the Gulf of Mexico. And

ammonia from fertilized cropland has become a major source of air

pollution, while emissions of nitrous oxide form a potent greenhouse

gas.

These and other negative environmental impacts have

led some researchers and policymakers to call for reductions in the use

of synthetic fertilizers. But in a report published in the June 19

issue of the journal Science,

an international team of ecologists and agricultural experts warns

against a "one-size-fits-all" approach to managing global food

production.

"Most agricultural systems follow a trajectory

from too little in the way of added nutrients to too much, and both

extremes have substantial human and environmental costs," said lead

author Peter Vitousek, a professor of biology at Stanford University and senior fellow at Stanford's Woods Institute for the Environment.

"Some

parts of the world, including much of China, use far too much

fertilizer," Vitousek said. "But in sub-Saharan Africa, where 250

million people remain chronically malnourished, nitrogen, phosphorus

and other nutrient inputs are inadequate to maintain soil fertility."

Other co-authors of the Science report include Woods Institute Senior Fellows Pamela Matson, dean of Stanford's School of Earth Sciences, and Rosamond L. Naylor, director of the Program on Food Security and the Environment.

China and Kenya

In

the report, Vitousek and colleagues compared fertilizer use in three

corn-growing regions of the world--north China, western Kenya and the

upper Midwestern United States.

In China, where fertilizer

manufacturing is government subsidized, the average grain yield per

acre grew 98 percent between 1977 and 2005, while nitrogen fertilizer

use increased a dramatic 271 percent, according to government

statistics. "Nutrient additions to many fields [in China] far exceed

those in the United States and northern Europe--and much of the excess

fertilizer is lost to the environment, degrading both air and water

quality," the authors wrote.

Co-author F.S. Zhang of China Agriculture University and colleagues recently conducted a study in two intensive agricultural

regions of north China in which fertilizer use is excessive. Their

results showed that farmers in north China use about 525 pounds of

nitrogen fertilizer per acre (588 kilograms per hectare)

annually--releasing about 200 pounds of excess nitrogen per acre (227

kilograms per hectare) into the environment. Zhang and his co-workers

also demonstrated that nitrogen fertilizer use could be cut in half

without loss of yield or grain quality, in the process reducing

nitrogen losses by more than 50 percent.

At the other

extreme are the poorer countries of sub-Saharan Africa, such as Kenya

and Malawi. In a 2004 study in west Kenya, co-author Pedro Sanchez and colleagues found that farmers used only about 6 pounds of nitrogen

fertilizer per acre (7 kilograms per hectare)--little more than 1

percent of the total used by Chinese farmers. And unlike China,

cultivated soil in Kenya suffered an annual net loss of 46 pounds of

nitrogen per acre (52 kilograms per hectare) removed from the field by

harvests.

"Africa is a totally different situation than

China," said Sanchez, director of tropical agriculture at the Earth

Institute at Columbia University. "Unlike most regions of the world,

crop yields have not increased substantially in sub-Saharan Africa.

Nitrogen inputs are inadequate to maintain soil fertility and to feed

people. So it's not a matter of nutrient pollution but nutrient

depletion."

U.S. and Europe

|

|

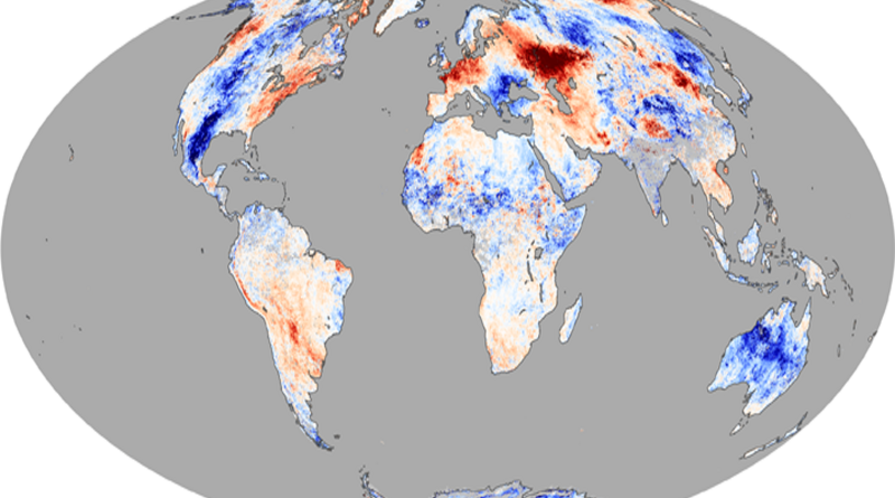

A comparison of 3 agricultural areas of the world found massive

imbalances in fertilizer use, resulting in malnourishment in some

regions and pollution in others.

Photo: David Nance, USDA |

The

contrast between Kenya and China is dramatic and will require vastly

different solutions, the authors said. However, large-scale change is

possible, they said, noting that since the 1980s, increasingly

stringent national and European Union regulations and policies have

reduced nitrogen surpluses substantially in northern Europe.

In

the Midwestern United States, over-fertilization was the norm from the

1970s until the mid-1990s. During that period, tons of excess nitrogen

and phosphorus entered the Mississippi River Basin and drained into the

Gulf of Mexico, where the large influx of nutrients has triggered huge

algal blooms. The decaying algae use up vast quantities of dissolved

oxygen, producing a seasonal low-oxygen dead zone in the Gulf that in some years is bigger than the state of Connecticut.

Since

1995, the imbalance of nutrients--particularly phosphorus--has

decreased in the Midwestern United States, in part because better

farming techniques have increased yields. Statistics show that from

2003 to 2005, annual corn yields in parts of the Midwestern United

States and north China were almost the same, even though Chinese

farmers used six times more nitrogen fertilizer than their American

counterparts and generated nearly 23 times the amount of excess

nitrogen.

"U.S. farmers are managing fertilizer more efficiently now," said co-author Rosamond Naylor, who is also a professor of environmental Earth system science and senior fellow at Stanford's Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies.

"The dead zone in the Gulf of Mexico persists due to continued

fertilizer runoff and animal waste from increased livestock production."

Low nitrogen in Africa

In

sub-Saharan Africa, the initial challenge is to increase productivity

and improve soil fertility, the authors said. To meet that challenge,

co-author Sanchez recommends that impoverished farmers be given

subsidies to purchase fertilizer and good-quality seeds. "In 2005,

Malawi was facing a serious food shortage," he recalled. "Then the

government began subsidizing fertilizer and corn seeds. In just four

years production tripled, and Malawi actually became an exporter of

corn."

Food production is paramount, added co-author G. Philip Robertson,

a professor of crop and soil sciences at Michigan State University.

"Avoiding the misery of hunger is and should be a global human

priority," Robertson said. "But we should also find ways to do this

without sacrificing other key aspects of human welfare, among them a

clean environment. It doesn't have to be an either/or choice."

For

countries where over-fertilization is a problem, the authors cited a

number of techniques to reduce environmental damage. "Some of

these--such as better-targeted timing and placement of nutrient inputs,

modifications to livestock diets and the preservation or restoration of

riparian vegetation strips--can be implemented now," they wrote.

Designing

sustainable solutions also will require a lot more scientific data,

they added. "Our lack of effective policies can be attributed, in part,

to a lack of good on-farm data about what's happening with nutrient

input and loss over time," said co-author Alan Townsend,

an associate professor of ecology and evolutionary biology at the

University of Colorado-Boulder. "Both China and the European Union have

supported agricultural research that yields policy-relevant information

on nutrient balances. But the U.S. is particularly lacking in long-term

data for a country with such a well-developed scientific enterprise."

Even

in Europe, with its strong research programs on nutrient balances and

stringent policies for reducing fertilizer runoff, nitrogen pollution

remains substantial. "The problem of mitigation of excess nitrogen loss

to waters is not easily resolved," said co-author Penny Johnes, director of the Aquatic Environments Research Centre at the University of Reading, U.K. "Society may have to face some

difficult decisions about modifying food production practices if real

and ecologically significant reductions in nitrogen loss to waters are

to be achieved."

According to Vitousek, it is important in

the long run to avoid following the same path to excess in sub-Saharan

Africa that occurred in the United States, Europe and China. "The past

can't be altered, but the future can be and should be," he said.

"Agricultural systems are not fated to move from deficit to excess.

More effort will be required to develop intensive systems that maintain

their yields, while minimizing their environmental footprints."

Other

co-authors of the Science report are Tim Crews, Prescott College; Mark

David, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign; Laurie Drinkwater,

Cornell University; Elisabeth Holland, National Center for Atmospheric

Research; John Katzenberger, Aspen Global Change Institute; Luiz

Martinelli, University of São Paulo, Brazil; Generose Nziguheba,

Columbia University; Dennis Ojima, The H. John Heinz III Center for

Science, Economics and the Environment; and Cheryl Palm, Columbia

University.

This work is based on discussions at the Aspen Global Change Institute supported by NASA, the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation, and the

David and Lucile Packard Foundation; and at a meeting of the International Nitrogen Initiative sponsored by the Scientific Committee on Problems of the Environment.

"We were definitely surprised that the linkages between temperature and recent conflict were so strong," said Edward Miguel, professor of economics at UC Berkeley and faculty director of UC Berkeley's Center for Evaluation for Global Action. "But the result makes sense. The large majority of the poor in most African countries depend on agriculture for their livelihoods, and their crops are quite sensitive to small changes in temperature. So when temperatures rise, the livelihoods of many in Africa suffer greatly, and the disadvantaged become more likely to take up arms."

"We were definitely surprised that the linkages between temperature and recent conflict were so strong," said Edward Miguel, professor of economics at UC Berkeley and faculty director of UC Berkeley's Center for Evaluation for Global Action. "But the result makes sense. The large majority of the poor in most African countries depend on agriculture for their livelihoods, and their crops are quite sensitive to small changes in temperature. So when temperatures rise, the livelihoods of many in Africa suffer greatly, and the disadvantaged become more likely to take up arms."